Motobi

By the standards of mid-Fifties ltaly's etceterini array of little-known marques, Motobi is an obscure sub-plot to the ever-changing soap opera that forms the panorama of Italian motorcycling.

Characteristically, the company only existed because of a family row which saw Giuseppe Benelli walk out of the family factory in 1948 and cross the street to found his own rival marque, whose products were at first solely identified by a large letter 'B' on the fuel tank.

Giuseppe was the eldest of six brothers whose mother, Teresa, had set them up in the motorcycle repair business back in 1911, a prelude to them attaching the Benelli badge to their own range of bikes from 1921 onwards.

For more than a decade, the two companies coexisted in barely-suppressed enmity in the small city of Pesaro on the Adriatic Riviera, later home of such well-known names as Morbidelli, MBA, Sanvenero and, more recently, of course, the reborn Benelli marque now under the control of the Merloni family.

Giuseppe Benelli passed away in 1957 at the age of 78, leaving his sons, Marco and Luigi, to grapple with the task of keeping the company afloat in the wake of the birth of the Fiat 500 car, which brought the post-war boom in Italian motorcycling to an abrupt end.

Motobi (as it was known from the mid-Fifties onwards, or MotoBi if you're looking to score points in two-wheeled Trivial Pursuit) had soon carved itself a good slice of the booming Italian bike market. It offered a range of innovative models - initially all two-strokes, including from 1953 onwards a 200cc rotary-valve twin bearing the curious name of the B200 Spring Lasting (don't ask!). This featured a pressed-steel frame and an egg-shaped engine with finned horizontal cylinders and vertical downdraught carbs which established the trademark format of Motobi products for the future.

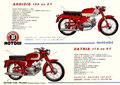

At the end of 1955, the company's first fourstroke models appeared, a pushrod 125cc and 175cc duo bearing the Catria name and designed by freelance engineer Piero Prampolini. His later credits included the 500cc four-cylinder GP Benelli, which Jarno Saarinen took to victory at its 1972 debut.

lnterestingly, the Catria's horizontal-cylinder engine layout preceded the arrival a year later of the similar-format 175cc Aermacchi Chimera. The Catria formed the basis for the backbone of Motobi's future four-stroke range, progressively upsized from the 62 x 57mm 175CC base version to an overbored 66.5 x 57mm 200CC 1963 model called the Sprite. Eventually, in 1966, there was a full 74mm-bore 250CC version whose Sport Special performance kit delivered 150 kph in road guise. The ohv single stayed in production until 1973, a year after the De Tomaso take-over by which time it was badged as a Benelli to form part of the Pesaro factory's 90,000-unit annual production. Before this, Motobi's fortunes had plummeted in the wake of Papa Benelli's death, and in November 1961, it was absorbed into the family empire, to form the Gruppo Benelli-Motobi. Peace had broken out, and for the rest of the decade, Motobi motorcycles were marketed as the more sporting lightweight products of the Benelli company, aiming to provide customers with a bike they could ride to work one day and compete with in their local hill-climb or road race the next.

The Motobi was a true production racer, tailor-made for success in Italy's thriving MSDS (Moto Sportive Derivate dalla Serie) Formula 3 category for Junior-class riders - sort of one step down from National-level racing. The Motobi was competitive in both the 125CC and 175CC classes, as well as in the 250cc category that came later Motobis won a total of 16 Italian Junior championships in the 1965, providing the steppingstone to a Grand Prix career for such famous names as Roberto Gallina, Silvano Bertarelli and future world champions Eugenio Lazzarini and Pierpaolo Bianchi. But the bikes were almost unknown outside Italy, except in the USA, where they were imported by Cosmopolitan Motors as part of their Benelli distribution deal. However, many of the models were re-badged as Benellis, or else sold through the giant Montgomery Ward department store chain as Ward Riversides. But Cosmo's controlling Wise family realized there was room to establish the Motobi name through competition, bringing in a handful of factory-developed Formula 3 racers for established names like Kurt Liebmann and Jess Thomas to compete successfully within North America. Thomas delivered Motobi's most illustrious moment when, with his 207cc Motobi, he defeated a pair of works RC162 Honda fours on the infield circuit at Daytona to win the 1962 US GP - not then a world championship event, bur still a prestige race.One of the men Benelli sent to America later in the decade to help Cosmo put Motobi on the map was a factory race mechanic named Eraldo Ferracci, who ended up staying on in the USA and carving out a bit of a reputation for himself. The man Ferracci had worked under in Italy was Primo Zanzani, a former racer from northern Italy who had been enlisted by Luigi and Marco Benelli to take over the Motobi race shop in 1957 on the death of their father. A self-taught tuner, Zanzani was the man responsible for turning the four-stroke family of Motobi models into such competitive hardware both in ltaly and the USA. This success earned him the task of developing the four-cylinder Benelli 250 GP racer from 1962 onwards, when the two companies were united. Having turned it into a Grand Prix race-winner in the hands of Tarquinio Provini, Zanzani moved back to Motobi in 1966. There he focused his attention on the new 250cc Sprite model introduced that year, with the specific purpose of making it a winner in the recently-introduced quarter-litre MSDS class for customers of the Pesaro factory.

The fact that Motobi won the Italian 250cc Junior title in 1966, '67 and '69 shows how well Zanzani succeeded. But by the end of the decade, competition was so intense from rival factories like Ducati, Parilla, Aermacchi and Morini that he had been forced to develop a limited edition homologation special known as the 'Sei Tiranti' (six-stud).

Produced in very limited quantities this had six cylinder head studs instead of the street Sprite's four, a factor which caused problems with cylinder head sealing when compression and engine speeds were raised in pursuit of power. Considering that by the end of the decade Zanzani had doubled the 16bhp output of the street 250 to 33bhp in MSDS form, this was hardly surprising. So an extra pair of studs was grafted in to bolt the cylinder head to what on this tricked-out special were sand-cast crankcases for extra stiffness, rather than the diecast ones of the streetbike. Make no mistake, this was for a silhouette c!ass, where every little trick was employed to gain an added edge. Bit like Supersport racing today, really....

Sadly, the Japanese onslaught meant diminishing sales and no budget for racing, so in 1970 the Motobi factory race department was closed, leaving Zanzani to start his own machine shop operation in Pesaro, where another 5 Sei Tiranti racers were built in the early '70S.

Zanzani later became a brake disc expert (see sidebar) but pressure from customers led to replicas of the old Motobis. "I was asked to make so many parts for Motobi enthusiasts either restoring or racing classic bikes. It seemed natural to consider building complete motorcycles again," recounted Primo, bending to adjust the clutch on the latest of the five Sei Tiranti replicas he's built so far in his Pesaro workshop. We sheltered from the torrid summer sun in the shadow of the pits at the Magione circuit near Perugia as Primo added: "After all, I still had all the jigs and patterns from when I built them in the old days, so restarting production didn't entail much preparation."He also has access to original Motobi parts stocks in both Italy and the USA, where Cosmopolitan Motors are marketing the modern Zanzani-built replicas to American historic racing enthusiasts.

This means that Primo can deliver a brand-new 250 Sei Tiranti to order in just 90 days, at a price of Lit.32 million + tax in Italy (about £11,500). Given that these are faithful in every detail to the original Motobi Formula 3 MSDS design, they're not so much replicas as the resumption of manufacture a quarter-century down the line of the original product.

Imagine if Colin Seeley himself were to restart construction today of his 7R/G50-powered racebikes. Same deal.To produce the modern Sei Tiranti, Zanzani takes a period Motobi pressed-steel spine frame chassis (produced in large quantities, as it was common to all the pushrod four-stroke models), and reinforces it with his own tubular steel bracing, which effectively constitutes a subframe attached to the main structure."We lengthened the wheelbase slightly by 30mm from standard to 1320mm in the 1960s with a special swing-arm," says Zanzani. "This improves stability in fast turns and increases weight on the front wheel for extra grip in slower ones."The new bikes have the same mod, with twin Works Performance gas shocks sourced from the USA, available with a choice of springs to suit 70,75 or 85 kg. rider weights.

The 35mm Ceriani forks are ubiquitous period hardware for a bike like this, with braking provided by a 210mm Fontana 4Ls front drum and 160 mm Grimeca 2LS rear, though with the complete bike weighing just 96 kg. complete with trademark 'double-bubble' fairing, and the fuel tank with its distinctive upward sweep to the steering head empty of fuel, there's not much to stop. Well, until you add the rider, that is....Actually, I fitted the Motobi better than I expected, and that's not just because I spent so many seasons at the outset of my racing career riding its Aermacchi rival of similar stature and cloned engine layout. I mean, that was, er, some years ago - though I must admit that folding myself with some success around a Ducati Supermono of similar horizontal cylinder layout for the past six years might have helped.On the freshly-constructed factory bike, the choice of a wider WM2 Akront rim for the rear 110/80 Avon AM23 tyre prevented it feeling too nervous or light-steering, whereas a customer's period bike I also sampled at Magione had the same tyre on a WM1 rim. The result was that it felt like riding my old Aermacchi on Dunlop triangular! I mean - twitchy!The new racer felt more stable and steered well (compared to the period machine), just the nimble side of nervous, and great in Magione's tighter turns, while still adequately stable in the one fast sweeper. But I did catch myself holding my breath as I cranked through it - not because I frightened myself, but because you're conscious that this is an ultra-agile motorcycle with not a lot of weight on the front wheel. You want to avoid upsetting it with any undue movement-such as a sharp intake of breath, for example... Only kidding (weIl, mostly)!

The American rear shocks worked really well, helping to deliver the ideal grip of the Avon tyres that are the benchmark products for today's classic racer. There was no chatter or slides, even in the torrid 35-degree heat of our test day, but the Ceriani forks were too softly damped, producing a bounciness that could be improved with heavier weight oil and or more of it. The 4LS Fontana front drum had quite a bit of bite, but only if you squeezed hard. The same brake on the customer bike I rode worked much better - perhaps because it wasn't as new and the linings had bedded in. But more likely, it had a different ratio on the lever pivot, as well as a longer lever. In any case, you need to use the rear 2LS Grimeca to maximum advantage to make the bike stop from any speed - just as on my series of Aermacchis, which I was so strongIy reminded of riding the Motobi.

Unlike the Varese-built bikes, the Motobi could never be increased in capacity to 350cc and even more because of its ultra short-stroke dimensions, even in the 175cc form in which the 'Uovamotore' (literally, egg-engine) was originally designed. There's no room between the camshaft and conrod at bottom dead center (BDC) to make the engine any bigger, says Primo Zanzani. The 72 x 61mm Aermacchi 250 didn't have this problem, even though the 32 bhp at 9,400rpm at the gearbox which this delivered in stock form, compared favorably with the 33bhp at 10,500 at the rear wheel which Primo has extracted from the born-again Motobi 6T's 74 x 58mm motor.

To achieve this, he takes new sand-cast crankcases and fits a stronger roller-bearing crankshaft with external flywheel, an Asso piston delivering 11.1:1 compression and a revised camshaft and rocker arm design. A Carrillo rod is an option available to customer spec, while the cylinder head is ported and flowed. It's then fitted with oversize 40mm inlet and 34mm exhaust sodium-filled Zanzi valves made to aircraft quality, set at a 10-degree steeper angle than on the road 250, and fitted with US-made RG springs.

America also provided the Crane Cams CDI ignition, which requires a healthy 12V battery (my running-in time on the new factory bike was extended until Primo finally found one that held its charge!), while carburation comes from a period 38mm Dell'Orto SSi with remote float, and no idle jet. Add in a close-ratio five-speed gearbox (there's a choice of alternative ratios available, such as a longer second) which retains the road bike's oil-bath clutch, as was required under period MSDS rules - and go. I did. WeII, only after finding a battery that worked properly and a hard enough plug to let the bike rev hard - but once that was sorted out, the Motobi delivered. lt pulls okay from as Iow as 4,000rpm, which is a bit of a surprise, but then there's a patch of megaphonitis, which means you need to keep it turning above 7,000rpm even in tight turns, achieved with a slight touch of the quite sensitive clutch lever.

The carburettor slide and cable on this brand new bike were still very sticky meaning that in the absence of any graphite grease to free up the throttle, getting on the gas to drive out of a turn was a rather jerky pickup as weIl as a hard twistgrip action. But the customer bike I rode, fitted with a Zanzani Sei Tiranti motor, showed how welI the package turns out, with an appetite for revs on this pushrod motor that I only ever remember seeing safely on my works-spec ultra short-stroke Aermacchi.

The best compliment I can pay the Zanzani Motobi is that riding it reminded me of that. Judging by my Magione spin, his customers can enjoy 11,000 rpm power deliveries reliably, according to Primo, and with a surprising turn of speed for a 250 pushrod single of 220kph at Monza.

But you must rev it hard to get competitive power. The fact that Zanzani holds ample stocks of all spare parts for engine and chassis (except Akront wheel rims) is a good reason to consider buying a new bike from the man who made them back then. That's if you want to go classic racing with peace of mind. Really , the Zanzani-built Motobi 250 is the lightweight version of the replica Manx Nortons and 7R/G50s built today for the bigger classes that dominate the grids of classic races around the world. In delivering the same option to enthusiasts of the smaller classes, Primo Zanzani is providing a service that others may follow - but few will be able to do so with the same enthusiasm and unbroken line of heritage that his modern Sei Tiranti racers undoubtedly represent.

1968 Motobi 50 America Source

Motobi 200 Spring Lasting Source

1972 Motobi 250 Sport Special Source

Ardizio 125cc 2T and the Catria 175cc 4T Source

Imperiale 125cc 4T and the Catria Scooter 175cc 4T Source

From Brakes to Bikes

In paralle with this, Zanzani developed a specialist expertise in the disc brake technology then new to motorcycles. He'd been the first in the world to adopt them on a GP racer back in 1965 on the four-cylinder Benelli, using US made Airheart discs rather than the cable operated Campagnolo brakes produced in ltaly for lightweight machines.

Zanzani developed his own process for plasmaspraying aluminium disc rotors with iron to produce a far lighter disc brake package than the steel or cast iron discs then commercially available. These discs offered notable benefits in terms of reducing unsprung weight and gyroscopic effect. His brakes became ubiquitous components on GP racers in the smaller classes, winning no less than 24 world championships in the 50/80/125/250cc classes from 1978 onwards, up to and including Alessandro Gramigni's 125 Aprilia World crown in 1992.

Today with his two sons at the age of 77, Primo Zanzani concentrates on running the trio of high-tech machine shops his family owns in Pesaro, producing intricate components for the local woodworking machinery industry - and Motobi 250 Sei Tiranti replicas!

External Links

Send what you have to:

| Motorcycle Information and Photos by Marque: A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z |

| Car Information and Photos by Marque: A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z |